Level 5 leadership was defined as the highest form of leader and the style present in all the great companies and in none of the comparison companies.

Twenty-three years after its initial publication, Good to Great by Jim Collins remains one of the bestselling business books of all time. The book’s intent was to answer a question that was nagging Collins, “What makes a company great?” The catalyst for pursuing the answer was the popular phrase “Good is the enemy of great,” which recognizes there are many good companies out there, but few that make the leap to being truly great. After years of analysis and research, Collins and his team of researchers concluded that there are a handful of traits that were commonly present among the 11 identified great companies (according to their definition of great).

One of the categories of findings was related to leadership and led them to develop a matrix of five distinct levels of leadership based on the behaviors and styles of the CEOs of the companies they studied. Level 5 leadership was defined as the highest form of leader and the style present in all the great companies and in none of the comparison companies. What is a Level 5 leader? As defined by Collins, the Level 5 leader is someone who combines both personal humility and unshakable will.1

More recently, the value of this leadership attribute to success was confirmed by Adam Grant in his 2021 book Think Again. Grant cites some extensive leadership studies in both the United States and China that concluded “the most productive and innovative teams aren’t run by leaders who are confident or humble. The most effective leaders score high in both confidence and humility.”2

While the eleven CEOs highlighted in Good to Great would be unfamiliar to 99 % of book’s readers due to their low-key approach to their jobs, the Level 5 Leader ideal has been exemplified by some of the most famous leaders in U.S. history.

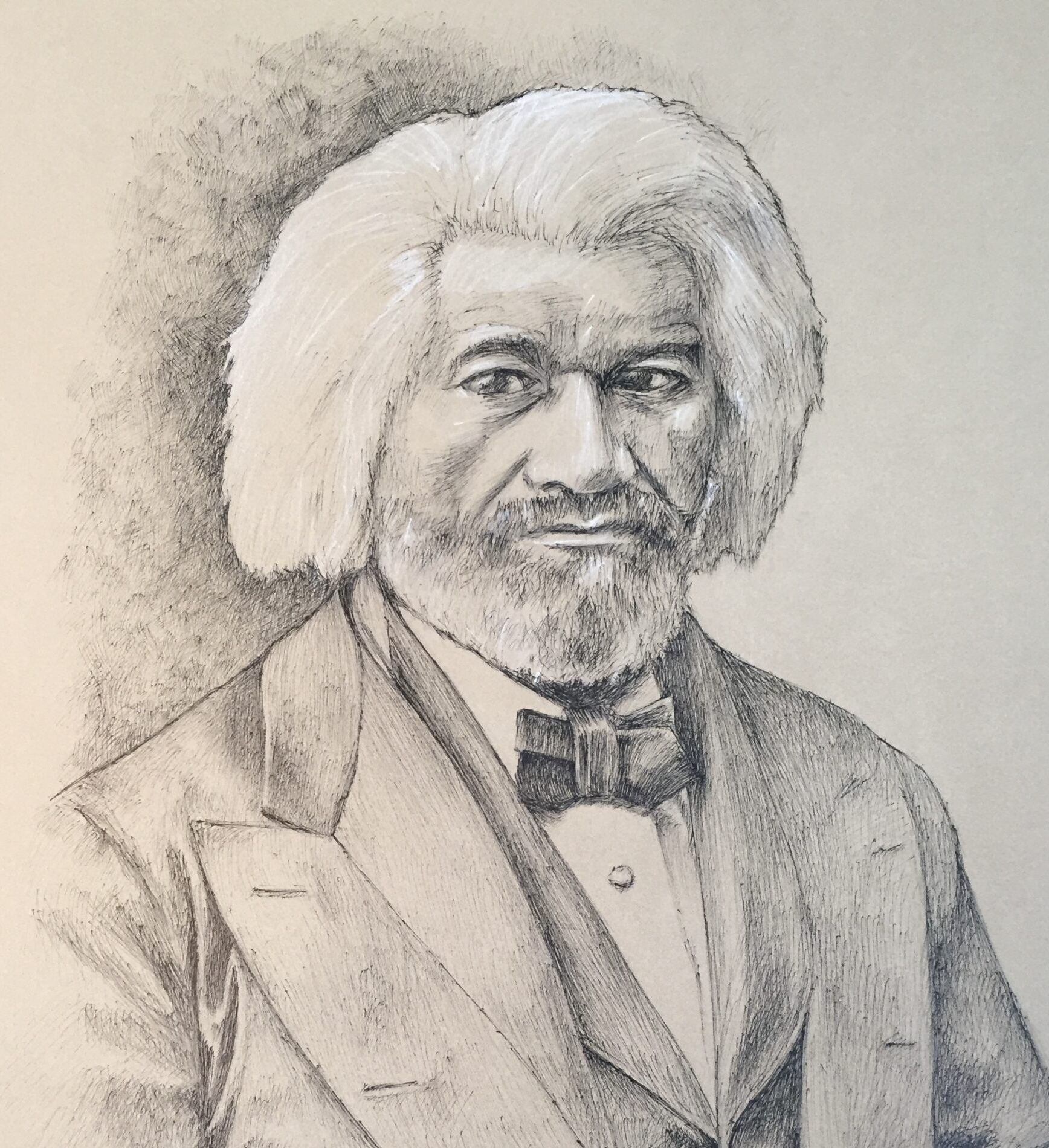

One such leader was Frederick Douglass, a former slave in the mid-nineteenth century who became one of the best-known champions of the abolitionist movement due to his skill at inspiring oratory. He was only able to accomplish great things in his adult life because, as a young boy trapped in slavery, he was taught to read and write by his mother and thus was able to expand his mind. Reading and writing were forbidden for most slaves because their owners believed (correctly) that it would stir a longing for liberty. Upon discovery of Douglass’s ability to read at age sixteen, his owner sent him away to a man known as a “slave-breaker” who would treat him with extreme cruelty to break his spirit. After four years of humiliation and beatings, Douglass escaped his life of slavery at the age of twenty. He fled to New York and later Massachusetts and soon realized that “I lived more in one day [as a free man] than in a year of my slave life.”3

In his own autobiographies, it is clear that Frederick Douglass possessed tremendous confidence in his own abilities and had great moral pride in the truth of his philosophical positions. But he also possessed a humble nature that flowed from seeing himself as subject to his God and to the founding ideals of his country represented by the Declaration of Independence. While Douglass understood that America was not living up to its ideals expressed in the Declaration, he had faith that it could.

During Douglass’s years traveling the north speaking and meeting with people in the cause of abolition, he was often humiliated, harassed, and even beaten. On one such trip, Douglass was made to ride in the baggage car of a train in Pennsylvania though he had paid for full passage the same as all the white passengers. Some white passengers on the train came to Douglass and apologized for him being degraded in that manner. Douglass responded, “They cannot degrade Frederick Douglass. The soul that is within me no man can degrade. I am not the one that is being degraded on amount of this treatment, but those who are inflicting it upon me.”4 Douglass had the strength of will to push through the many barriers thrown up against him because he also had a level of humility regarding the importance of his mission to gain freedom and equality for his fellow enslaved people.

Abraham Lincoln was a contemporary of Frederick Douglass, but in contrast had true power and a much greater ability to affect major events. Though Lincoln’s humble beginnings are legendary, his early business partner, William Herndon, spoke of Lincoln as being highly ambitious and, to some degree, lacking humility. Even Lincoln admitted, “I claim no extraordinary exemption from personal ambition.”5 However, personal ambition at the level that Lincoln showed is common among most people, but especially for those who rise to leadership positions. Lincoln’s early life and its hardships informed his empathy towards those without power or prestige who needed and deserved all the Constitution’s protections of individual liberty. Speaking to soldiers of an Ohio regiment during the height of the Civil War, Lincoln said: “Nowhere in the world is presented a government of so much liberty and equality. To the humblest and poorest amongst us are extended the highest privileges and positions. The present moment finds me at the White House, yet there is as good a chance for your children as there was for my father’s.”6 Lincoln’s humility was combined with his strong conviction that the Union must be preserved and that it must experience a new birth of freedom. His combination of personal humility and unwavering will is undeniable. Considering the racial inequality that was present during the Civil War era in America, the fact that Lincoln treated Douglass with dignity and respect speaks loudly of his personal humility. When Douglass was denied entry to Lincoln’s post inaugural reception, Lincoln quickly made sure he was admitted into the White House and greeted him in front of all his guests, saying “Here comes my friend.”7

Good to Great includes some interesting background on the research team’s process. From the beginning of the project Jim Collins resisted any focus on analyzing the role of the leader. He believed that it was simplistic to “credit the leader” or “blame the leader” and specifically cited as his reasoning that, man, until around the 1500’s explained everything in terms of “God did it.” He stated that with the Enlightenment, man began to look to scientific methods to explain the previously unexplainable and he wanted to make his book a result of scientific study without any nods toward leadership qualities. What happened, though, was that his research team continued to come back to him to claim that their data analysis clearly showed a pattern of leadership in the 11 great companies that was lacking in all direct comparison companies. Collins eventually relented and decided the data must inform the conclusions even though he specifically held an adversarial opinion of anything that implied that “God did it.”8

Ironically, when I first read about the Level 5 leader principle in Collins’ book, it immediately made me think of the leadership attributes of Jesus. This is not a blind “God did it” statement, but an assessment of the man and his actions and how he approached his relationships with his friends and followers. Any student of the Bible would understand that Jesus’ life was defined by humility combined with the unwavering strength of will to speak the truth and complete his mission, no matter the cost. Just one example of this combination of humility and will was expressed when Jesus washed his disciples’ feet.

“Jesus knew he had come from God and would go back to God. He also knew that the Father had given him complete power. So, during the meal Jesus got up, removed his outer garment, and wrapped a towel around his waist. He put some water in a large bowl. Then he began washing the disciples’ feet.” John 13: 3-5

The first two sentences in this passage express the fact that Jesus did not assume this humble position with his disciples because of any emptiness or low self-esteem. He knew who he was and where he came from and was empowered to humble himself as an example of servant leadership. There is also no question that he was unwavering in his commitment to the mission he came to fulfill which resulted in his own painful death. The fact that people were willing to walk away from their livelihoods and even their families to follow Jesus is strong proof of his leadership appeal.

The work of Jim Collins, Adam Grant, and many other behavioral researchers bolster the argument that people are created or wired in a certain way to be drawn by our very nature to certain styles of leadership. The Level 5 leader is exemplified by many historic and current examples, but the life of Jesus displays it more than any other. The combination of humility and unshakable will is an unbeatable leadership recipe for success.

*** Note on accompanying image. This is a drawing of Frederick Douglass I completed in 2017.

Notes:

1 Jim Collins, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap … and Others Don’t, (New York, HarperCollins Publishers, Inc.), 22.

2 Adam Grant, Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know, (New York, Penguin Books), 48.

3 David J. Bobb, Humility: An Unlikely Biography of America’s Greatest Virtue, (Nashville, TN, Nelson Books), 173.

4 Ibid., 181.

5 Ibid., 128.

6 Ibid., 138.

7 Ibid., 156.

8 Collins, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap … and Others Don’t, 21.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.